Eliška Konečná

Thirst

20.9.2023–4.11.2023 Prague Curated by Caroline Krzyszton- text (EN)

- text (CZ)

THIRST

What is fascinating about Eliška Konečná's work is that it detaches itself from any chronological linearity to gradually approach a certain timelessness, a form of universalism mirroring the history of art.

This interpretation finds its roots in Eliška Konečná's relation to symbolism and the almost classical construction of her narration around allegorical figures. The artist seems to slowly develop her personal mythology filled with characters depicted for their individual qualities, struggling with morality issues, while she uses a very intuitive language, leaving a great place for pure aesthetic considerations. In this sense Eliška Konečná's practice definitely illustrates a certain return to sensuality.

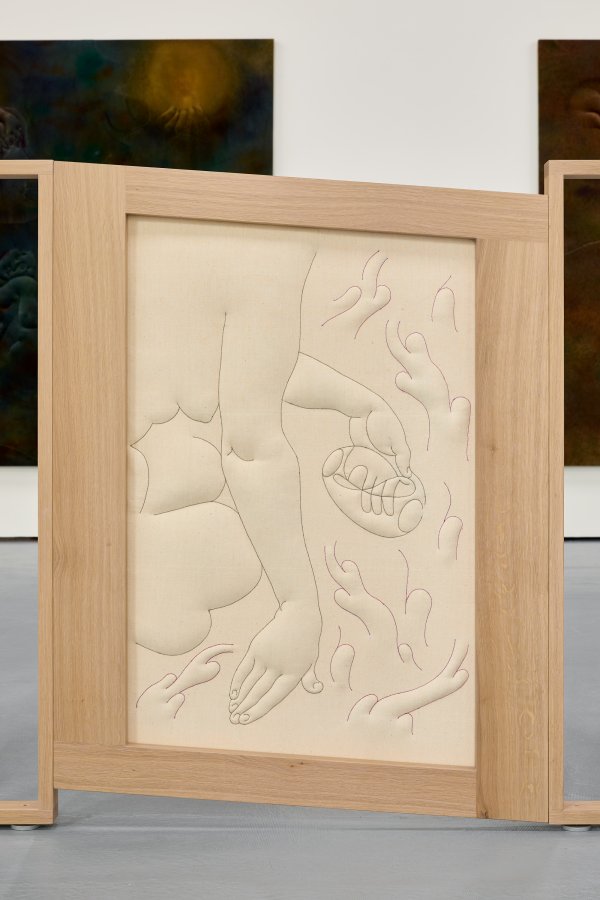

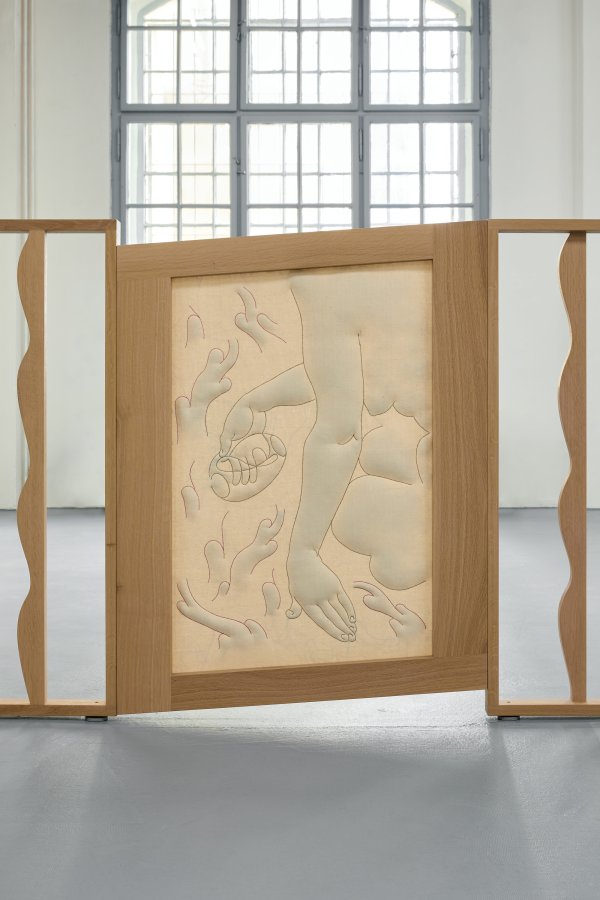

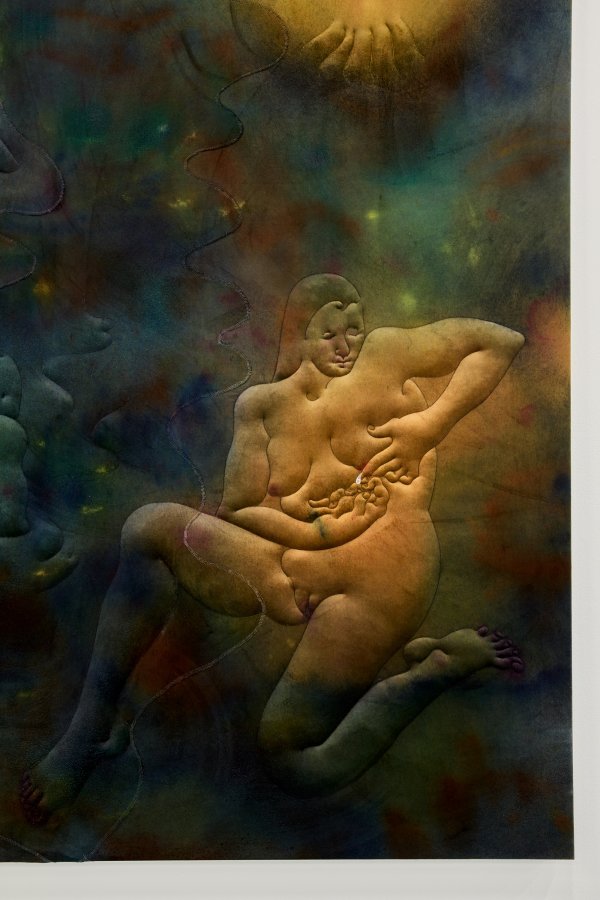

This project is the continuation of the artist's previous exhibition at eastcontemporary gallery in Milan titled A Dry Place to Fall, where one could already view The Great Sleep (Velký Spánek), the first of three large textile bas-reliefs constituting the triptych of Thirst.

At Polansky were added The Great Feast (Velká Hostina) and The Great Bath (Velká Koupel) as the two missing scenes from the final artwork.

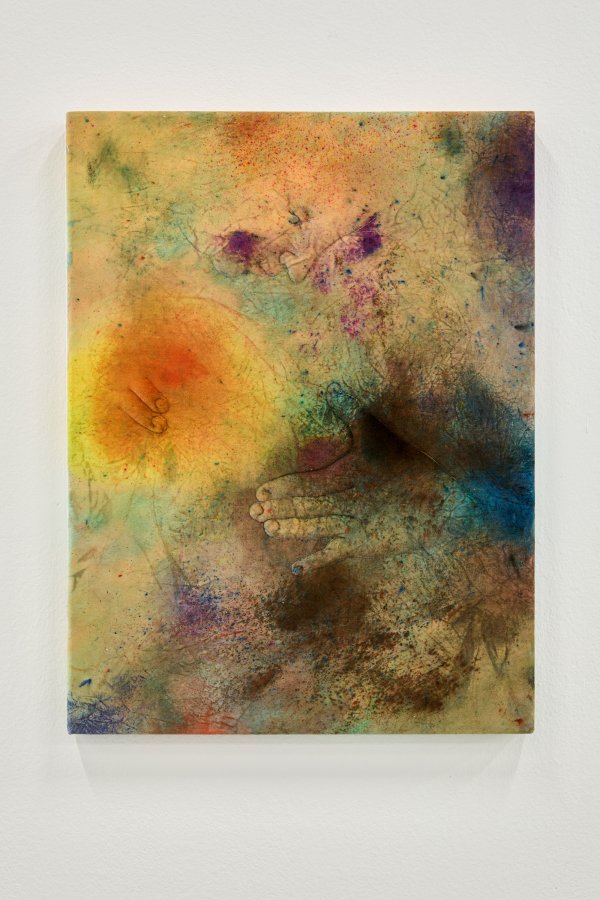

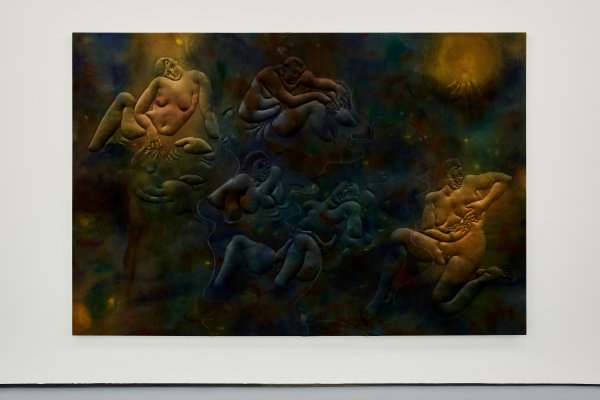

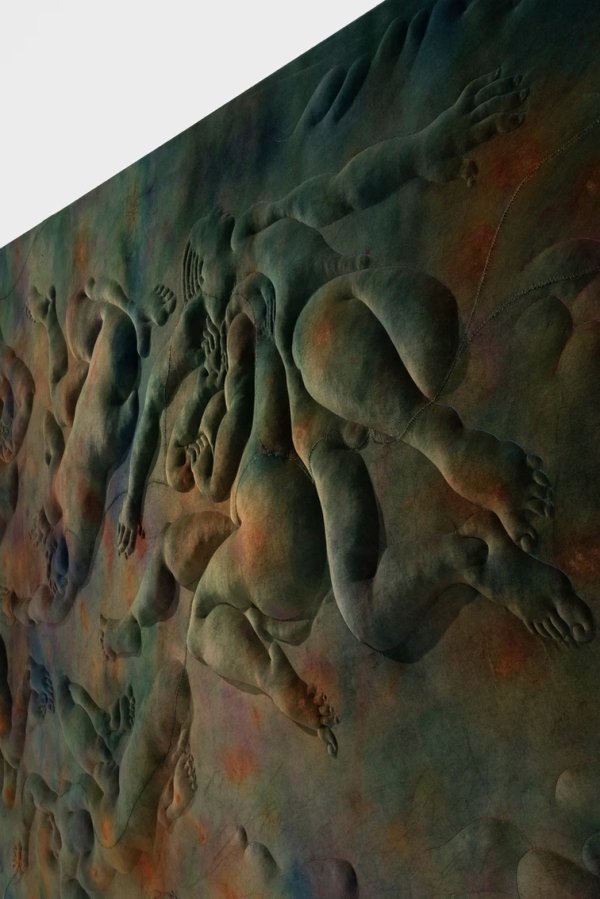

If Eliška Konečná has been using this media for several years now, this body of work is definitely the one where she has used the most figurative drawing and most abundant use of color, as if the overlapping painting coexisted alongside the sewn drawing as its own independent narrative, its abstract counterpart, or its palimpsest.

The two artworks constituting the side panels of the triptych, The Great Sleep and The Great Bath both find the figure of a breastfeeding woman as their main character: a tormented mother offers her milk to an abandoned baby bird. This useless attempt to save a life is performed in front of an audience of secondary characters that either sleep (The Great Sleep) or stare at her (The Great Bath). We, as the gallery audience, notice both the woman's great despair and the lack of care or the schadenfreude of the other characters, as the scene's third perception angle.

At the center, in The Great Feast, all characters are placed in a circle composition within which lines make uncertain whether they feed each other or if they prevent other ones to have access to food, whether they are offering or taking. On the foreground, one of them suffocates himself. But we stand in front of him without empathy.

Indeed, Eliška Konečná's scenes are not joyful nor sad, we observe her characters at a distance, as we would stay behind a fence, helpless but curious, how the story unfolds.

Her characters, as antique gods, make unavoidable human mistakes, they give in to temptation, they let primary needs hinder their judgment. Their bodies exist both as the manifestation of their desire and the vessel of their punishment.

In Eliška Konečná's artworks, emotion is treated as a background of sensuality, or as its direct consequence. If her subjects often illustrate a notion of impossibility, their pain and guilt is opposed with resignation and acceptance, as eventually the bodies, limited by their own humanity, are transcended by their ability of neutrality.

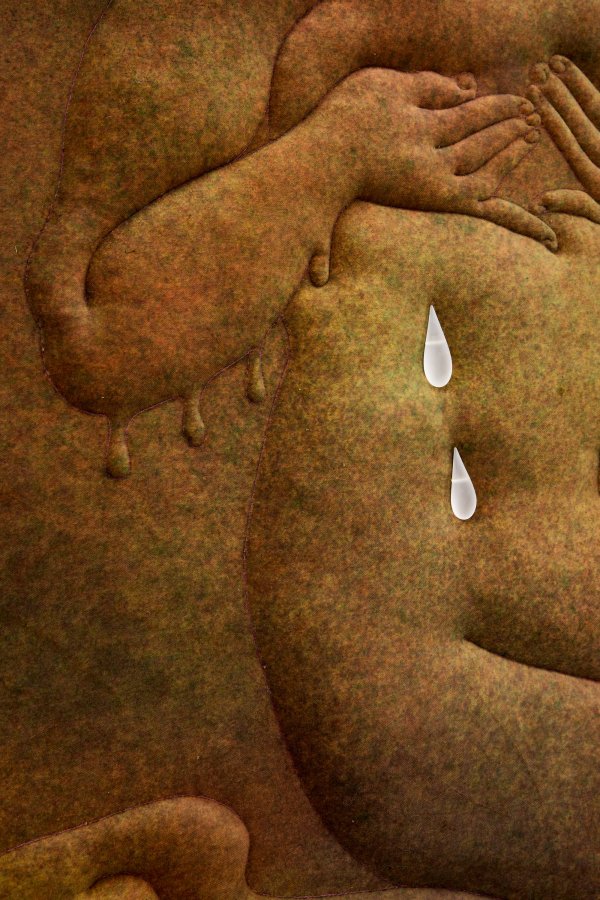

Life and death here are described contextually, in situations where water flows, or where it is missing. Such as The Fountain suggests, water may be shortly contained but it is never imprisoned, it wipes away as much as it draws shapes. Water also never disappears, it escapes and transforms. It can forget.

And as the bodies wash themselves in The Great Bath in a possible attempt for forgiveness, the artist lets us glimpse at eternity in a drop of water.

Caroline Krzyszton

ŽÍZEŇ

Tvorba Elišky Konečné je fascinující svým odpoutáním od jakékoli chronologické lineárnosti, čímž se postupně přibližuje k určité bezčasovosti, jisté formě univerzálnosti zrcadlící dějiny umění.

Tento výklad má své kořeny v jejím vztahu k symbolismu a takřka klasické konstrukci její narace pomocí alegorických figur. Eliška Konečná jako by rozvíjela svou vlastní, osobní mytologii obsazenou postavami vyobrazenými s osobitými kvalitami, zápasícími s morálními otázkami, přičemž používá velmi intuitivní jazyk a ponechává značný prostor pro čistě estetické úvahy. Praxe Elišky Konečné v tomto smyslu definitivně ilustruje jistý návrat ke smyslnosti.

Tento projekt je pokračováním autorčiny předchozí výstavy v milánské galerii eastcontemporary s názvem A Dry Place to Fall kde již bylo k vidění dílo Velký Spánek, první ze tří velkoformátových textilní reliéfů tvořících triptych Žízeň. Pro výstavu v galerii Polansky byly přidány zbývající dvě části trojice, z nichž se skládá finální dílo: Velké jídlo a Velká koupel.

Používá-li Konečná toto médium již několik let, v tomto souboru bezpochyby hraje figurativní kresba dosud nejvýraznější roli, stejně jako hojnost barvy, jako kdyby malba přesahující prošívanou kresbu existovala po jejím boku jako vlastní nezávislá narativní linka, jako její abstraktní protějšek či palimpsest.

Hlavní postavou obou děl tvořících postranní panely triptychu, Velký spánek a Velká koupel, je kojící žena: soužená žena nabízí své mléko opuštěnému ptáčeti. Tento marný pokus zachránit život probíhá před publikem, jehož členové buďto spí (Velký spánek) nebo na ní upřímně hledí. Jako galerijní diváci vnímáme hloubku matčina zoufalství i lhostejnost ostatních postav, či jejich škodolibost, čímž vzniká třetí úhel pohledu na výjev jako celek.

Všechny postavy v centru díla Velké jídlo jsou umístěny do kruhového útvaru, z linek v něm obsažených však není jasné, zdali si postavy jídlo vzájemně nabízejí či odpírají. V popředí se jedna z nich dusí. Když však před ní stojíme, nevzbuzuje v nás empatii.

A vskutku, výjevy Elišky Konečné nejsou radostné ani smutné, pohlížíme na její postavy s odstupem, jako kdybychom se nacházeli za plotem, bezmocní, ale přitom zvědaví, jak se příběh vyvine. Její postavy podobně jako starověcí bohové nevyhnutelně a lidsky chybují, podléhají pokušení, dovolují svým primárním potřebám, aby převážily nad soudností. Jejich těla existují jako projev touhy i nádoby vlastního trestu.

V dílech Elišky Konečné je k emocím přistupováno jako k zázemí smyslnosti, či jejího přímého důsledku. Jsou-li její postavy často ilustrací určité představy neuskutečnitelnosti, protikladem jejich bolesti a pocitu provinění je odevzdanost a smíření, jelikož jejich těla, omezena vlastní lidskostí, ve finálním důsledku projevují schopnost přesahu do stavu neutrality.

Život a smrt jsou zde popsány kontextuálně v situacích, kde se buďto voda vyskytuje v tekoucí formě, anebo není přítomna vůbec. Jak naznačuje práce Fontána (jedna z prvních dřevěných soch, které umělkyně vytvořila), vodu lze na krátkou dobu udržet na jednom místě, ale nikdy se nedá uvěznit – kresby, které vytváří zároveň smývá. Voda navíc nikdy nezmizí, pouze uniká, ztrácí paměť a transformuje se.

A ve chvíli, kdy se těla ve Velké koupeli umývají v možném pokusu o dosažení odpuštění, nechává nás umělkyně nahlédnout do věčnosti v kapce vody.