Vladimír Houdek

Atilis Press

4.9.2020–24.10.2020 Prague- Text by Vojtěch Märc (EN)

- Text by Vojtěch Märc (CZ)

“Literature to date has told us of fictitious characters. We shall go further: we shall depict fictitious books. Here is a chance to regain creative liberty, and at the same time to wed two opposing spirits—that of the belletrist and that of the critic.” With this claim, Stanislaw Lem introduces his work A Perfect Vacuum, a book consisting of reviews of books that were never written. Here, Lem is using a device that enables him to be both author, and protagonist. He writes about non-existent books and at the same time he is the one creating them. He attributes them to other authors, and yet they are his books. When, several lines down, he expresses the suspicion that “a more serious matter is at stake here—that of unfulfillable desire”, he indicates that the position, or place, he is taking up is just as impossible, as it is necessary. The picture on the cover of the 1983 Czech translation of A Perfect Vacuum published by Svoboda in its Jiskra edition may be of just such a place. The Zdeněk Ziegler collage depicts an incomplete outline of an upside-down female face. On the face, at the line between her straight nose and lipstick-painted lips, the names of the author, book and edition take up their position. Instead of an eye, we see an indeterminable object. It is a dimpled cylinder that reminds us of part of a tool or piece of equipment. At one of its ends, it blends into a series of wrinkled, black and white op-art lines themselves connected to a hardly visible lock of hair.

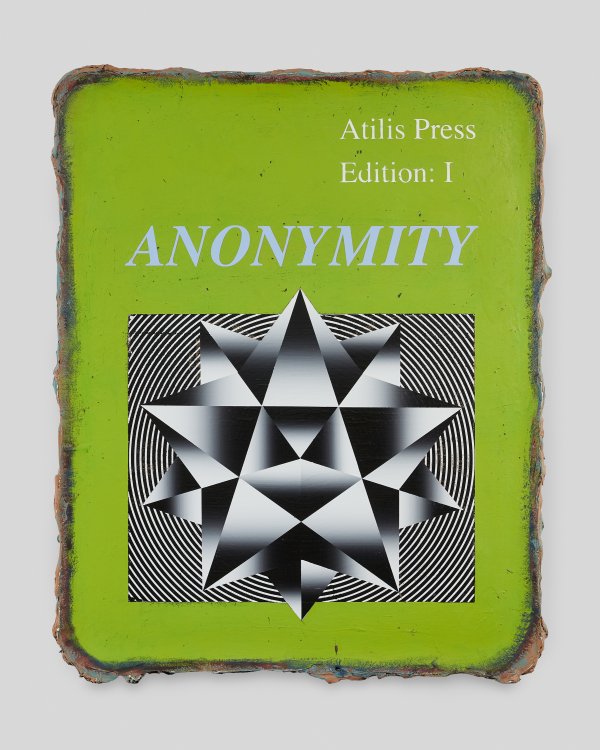

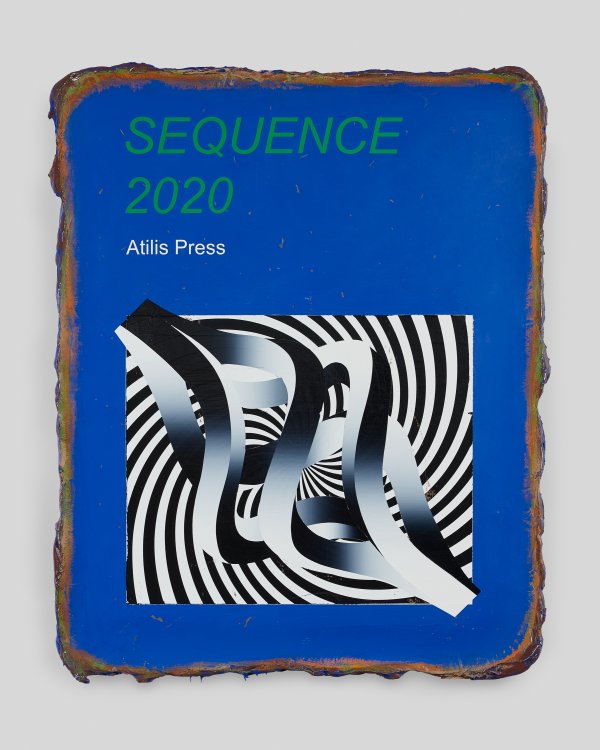

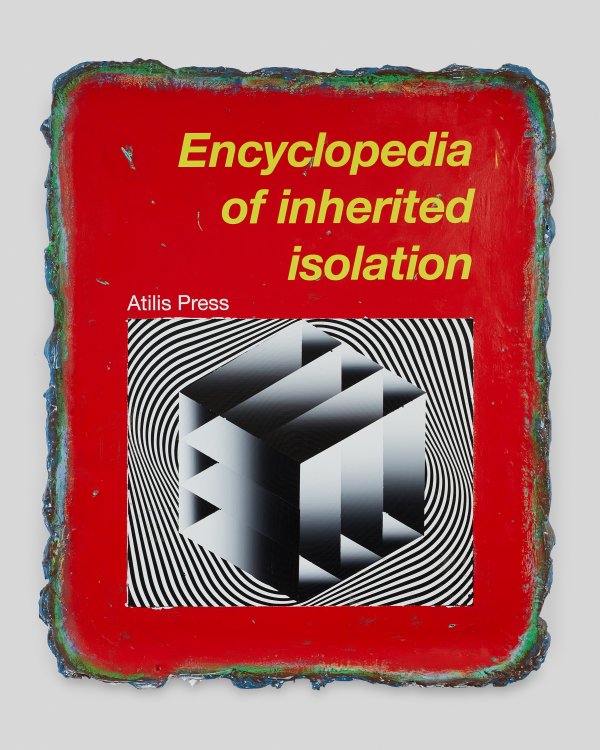

Perhaps the book cover will sound familiar to the those who regularly see Vladimír Houdek’s paintings more because the list of its elements, rather than its overall impression. For his new series entitled Atilis Press, Houdek expands the scope of his work with collage, op-art surfaces and abstracted objects to include book covers produced by a fictional publisher. Although Houdek did not use Ziegler’s cover of Lem’s book as the blueprint for his paintings, it may provide a manual for looking at, or understanding, them. As with A Perfect Vacuum, they stretch from something real to something unreal; an “unfulfillable desire”. It is precisely this impatient endeavour to fill an emptiness that according to art historian Christopher Wood has led to the situation where many today prefer to talk about images or things, rather than artworks. A certain power is then attributed to images and objects; an ability to act. This power is meant to replace something lacking in works of art – an immediate connection to reality. This is exactly where Wood discerns the very precondition of art. At the same time, he concedes that in view of this deficiency, works of art have no other option but to internally find their own designation in relation to images and things. Artworks always reveal their contents too late (as an image), or not at all (as a thing). They are both of the above, without exhausting their possibilities to be more in the process.

Book covers may then also be viewed as an interface. They are the place of contact between the outside and the inside of a book, as if they were both part of it and something else at the same time. They are simultaneously an image, a title and a thing: they offer themselves up to be seen, read and handled in the different ways we use to arrange the world around us, as well as ourselves. In Houdek’s rendition they are in addition something much more, despite the fact – or precisely because of it – that he is questioning the matter-of-course nature of familiar systems. Painted books cannot be read, just as objects depicted on their covers cannot be grasped. They show themselves in an unreal light. Like strange instruments they presuppose sensory experience, and yet they are heading somewhere beyond it. By refuting it, they confirm utopia.

1/ See the 1979 English edition of A Perfect Vacuum by Stanislaw Lem, translated from the Polish by Michael Kandel, North Western University Press.

„Literatura nám doposud vyprávěla o fiktivních postavách. My půjdeme dál: budeme popisovat fiktivní knihy. To skýtá možnost znovu nabýt tvůrčí svobody a současně spojit sňatkem dva protichůdné duchy – beletristu a kritika.“ Takovým tvrzením uvádí Stanisław Lem svou Dokonalou prázdnotu, knihu sestávající z recenzí na nikdy nenapsané knihy. Lem tím provádí úskok, jenž mu umožňuje zajmout jak místo autora, tak i protagonisty. Píše knihu a zároveň píše o knize. Píše o knihách, které nikdy nevznikly, a přitom je vytváří. Připisuje je jiným autorům, a přece jsou jeho. Když o několik řádků níž vyslovuje podezření, „že se jedná o vážnější věc, a to o neuskutečnitelnou touhu“, naznačuje, že místo, které obsazuje, je stejně nutné, jako nemožné. Obraz takového místa by mohla vyjevit knižní obálka, s níž v roce 1983 vydalo nakladatelství Svoboda v edici Jiskry český překlad Dokonalé prázdnoty. Koláž od Zdeňka Zieglera ukazuje neúplný profil ženského obličeje obraceného hlavou dolů. Na tváři v úrovni mezi rovným nosem a namalovanými rty spočívá jméno autora a název knihy i knižní edice. Namísto oka je vidět neurčitelný předmět. Válec opatřený jamkou připomíná část nějakého nástroje nebo zařízení. Jeden jeho konec se ztrácí v černobílém op-artovém zvrásnění, které navazuje na sotva viditelný pramen vlasů.

Spíš ve výčtu prvků než v celkovém vyznění bude tato obálka povědomá divákům maleb Vladimíra Houdka. K práci s koláží, k op-artovým plochám a k abstrahovaným objektům přibývá v jeho nové sérii Atilis Press rámec obálek knih z produkce fiktivního nakladatelství. Zieglerova obálka Lemovy knihy sice asi nebyla Houdkovi vzorem k vytvoření těchto maleb, ale možná nabízí návod k jejich nazření. Podobně jako Dokonalá prázdnota se totiž s „neuskutečnitelnou touhou“ rozpínají mezi něčím skutečným a něčím neskutečným. Právě netrpělivá snaha o zaplnění této prázdnoty vede podle historika umění Christophera Wooda k tomu, že mnozí dnes radši než o uměleckých dílech mluví o obrazech nebo o věcech. Obrazům a věcem se pak přiznává jistá moc, určitá schopnost jednat. Tato moc má vynahradit to, čeho se nedostává uměleckým dílům, tedy bezprostřední spojení s realitou. Přesně v tom však Wood rozpoznává samotnou podmínku umění. Zároveň připouští, že s ohledem na tento nedostatek uměleckým dílům nezbývá, než se vnitřně určovat ve vztahu k obrazům a k věcem. Umělecká díla vždy vyjevují svůj obsah příliš prostě (jako obraz) anebo vůbec (jako věc). Jsou obojím, aniž by se tím vyčerpávala.

Knižní obálky lze potom nahlížet jako rozhraní. Prostředkují mezi vnějškem a vnitřkem knihy, jako by byly její součástí i něčím jiným. Jsou souběžně obrazem, nápisem i věcí: nabízí se k vidění, ke čtení i k zacházení coby různým způsobům, jimiž uspořádáváme svět i sebe samé. V Houdkově podání jsou ještě něčím navíc, a to navzdory tomu – anebo právě proto – že se tu zpochybňuje samozřejmost povědomých řádů. Namalované knihy se nedají přečíst, podobně jako se předměty vyobrazené na jejich obálkách nedají uchopit. Ukazují se v neskutečném světle. Jako podivné nástroje předpokládají smyslovou zkušenost, a přitom míří někam za ni. Potvrzují utopii tím, že ji popírají.